Abstrict

With the rise of social media over the last two decades, people have become more polarized and rigid in their views. Social interactions on social media networks are affecting political behaviors and making people obstinate partisans. The term obstinate partisanship was coined by Ardevol-Abreu and Gil de Zúñiga (2020) and referred to the blind, unconditional loyalty to a certain political party. The purpose of this study is to examine the prevalence of obstinate partisanship in Pakistani media users who are active consumers of political news and regularly engage in political discussions. This study seeks to investigate how significantly various factors impact obstinate partisanship. The factors studied are media use habits, affiliation with a political party, socio-demographic characteristics including age, gender, education, income, area of residence, and political discussion attributes. The survey data collected from the four major cities of Pakistan and their neighboring rural areas were used. The data revealed that the individuals who engage in political talk online and disagreements during discussions over political issues are more likely to remain unconditionally supportive of party policy and action regardless of their adequacy, the effectiveness of the policy and party performance and this disposition seems to increase with age.

Keywords

Offline Political Discussions, Social Media Use, Online Political Discussions, Echo Chambers, and Obstinate Partisanship

Introduction

Today, the internet gives people unprecedented access to information. In order to deal with the huge amount of news and information available, people develop their own repertoires by selecting the set of media consistent with their taste and the sources they trust (Guess, Nyhan, Lyons, & Reifler, 2018). Reliance on personal online repertoires, mainly social networking sites, commonly create an environment that allows ideas and information that reflect or reinforce users’ existing beliefs and limit opposing viewpoints. Social media, in particular, in addition to mobilizing information (Lemert, 1984), also provides a platform for discussion (Bae, Kwak, & Campbell, 2013; Vraga, Anderson, Kotcher, & Maibach, 2015) and thereby fuelling political partisanship (Yoo & Zúñiga, 2019; Dilliplane, 2011).

On social media platforms and other websites, such patterns are exacerbated by algorithms and the feature of ‘following’ that forms groups and communities, leading to homophily – a tendency to connect and socialize with people having similar ideas and beliefs. This results in an echo chamber effect which can be blamed for fostering extreme views among groups and individuals. The echo chamber is a metaphorical term used to describe a situation in which a media user tends to only encounter information that coincides with his or her ideas and beliefs (Dubois & Blank, 2018; Jamieson & Cappella, 2008). People in an echo chamber tend to discuss issues with others who have similar views, often drawing misinformed and distorted perspectives. (Du & Gregory, 2017; Cebrian, Rahwan, & Pentland, 2016; Guess, Nyhan, Lyons, & Reifler, 2018) The Echo Chamber effect is not only limited to media consumers; rather, it can be observed in the content creators as well. A study found that top bloggers, while discussing and commenting on political issues, frequently reference other similar bloggers and are often found using ‘straw-man arguments, i.e. reinforcing one’s argument by distorting the opposition’s viewpoint regardless of its merit (Hargittai, Gallo, & Kane., 2008; Tsang & Larson, 2016) consequently promoting one-sided views. In an echo chamber, the direction and intensity of political views are governed by two factors- - social influence and “controversialness” of the topic being discussed. These two factors also play a determining role in transforming moderate initial stance to extreme opinions in a homophilous social network (Baumann, Lorenz-Spreen, Sokolov, & Starnini, 2020; Chen, Shi, Yang, Cong, & Li, 2020, p. 4)

Moreover, increased homophily and lack of interaction with those having differing political views increase political polarization (Centola, 2013) and intolerance (Mutz, 2002a). Politically homophilous networks potentially reinforce groups’ behavioral norms, strengthen their political viewpoint and embolden members to take part in undemocratic perilous activities (Centola, 2013; Centola & Macy, 2007).

Research shows that individuals who are not exposed to diverse viewpoints are unable to recognize the legitimacy of opposing standpoints and are also less able to provide legitimate logic for their own political decisions. (Huckfeldt, Mendez, & Osborn, 2004; Price, 2002). Their lack of knowledge and understanding of other perspectives makes them prone to accept views and assessments unquestioningly. Such people tend to staunchly adhere to their political views and choices thus, become politically intolerant, stubborn partisans (Huckfeldt, Mendez, & Osborn, 2004); this attitude is termed as “obstinate partisanship” by Ardevol-Abreu and Gil de Zúñiga (2020). Obstinate partisanship is described as a “degraded outgrowth” of partisan attitudes emerging from “in-group and out-group” feelings, culminating in unconditional support to the party irrespective of party performance and policies (Ardevol-Abreu & Gil de Zúñiga, 2020, p. 325).

Moreover, individuals’ propensity to retain network relationships necessitates group conformity can lead to the development of extreme political attitudes in a group (Zhang, Wang, Chen, & Shi, 2020). Social-psychological approaches describe such tendencies to conform in terms of group identification. Individuals perceive political parties as their social group through which they partially define and express their identity (Smith & Mackie, 2007). The “we feeling” that party attachment gives surpasses other considerations and results in an enduring emotional connection. The political identity thus attained remains unaffected by external events, party performance or policy actions (Butler & Stokes, 1974, p. 37).

Obstinate partisanship is not a desirable trait; it eventually harms the political system as it renders opinions and votes devoid of any meaning (Ardevol-Abreu & Gil de Zúñiga, 2020; Bartle & Bellucci, 2014). However, it is argued that not necessarily every individual in the social media networks displays such extreme partisan behavior. Partially because in a social network, extreme information and views cause segregation and are thus unlikely to influence the majority opinion; moderate messages are more likely to be accepted by the general population, thereby producing the cohesion effect (Sîrbu, Loreto, Servedio, & Tria, 2013; Zhang, Wang, Chen, & Shi, 2020).

It is well documented that socio-demographic variables influence political behavior. Individuals are driven by group affiliations, and their political choices and leanings are in response to various “sociological pressures” and “cross-pressures” ensuing from differences in social class, religious and political affiliations, dwelling, etc. (Kanji & Archer, 2002, p. 161). The active and informed members within a certain demographic group try to influence the opinions and decisions of other less mobilized members of the group, consistent with the groups’ preferences. Individuals, in order to strengthen group association, try to acquire the same political preferences (Perrella, 2010).

Partisans Political Discussion on Social Media

Echo chambers in online settings can exacerbate political polarization by enabling mutually reinforcing opinions to push individual views towards extreme positions (Sunstein, 2002). For example, on Twitter, it is observed that when discussing highly politicized issues, like-minded users reply to each other way more than do users with opposing views, relishing in the group identity feeling (Yardi, 2010). Studies have indicated that when encountering differing views during a political discussion, certain individuals tend to deliberately go against the argument advocated by the other group and obstinately continue to support their party stance. Such behavior could be the result of the repulsion effect and attitude polarization (Gastil, Black, & Moscovitz, 2008; Zaller, 1992).

The purpose of this study is to explore the prevalence of obstinate partisanship in Pakistani media users who are active consumers of political news and regularly engage in political discussions. This study investigates how significantly various factors impact obstinate partisanship. Ten factors studied are; media use habits, affiliation with a political party, socio-demographic characteristics including age, gender, education, income, area of residence, and political discussion attributes. The political discussion attributes include the frequency of political discussion occurring online and offline and the frequency of encountered discussion disagreements. The hypotheses of the study are as follows:

H1: There is a significant impact of Media use habits on obstinate partisanship.

H2: Strong party affiliation is a significant predictor of obstinate partisanship.

H3: Age is a significant predictor of obstinate partisanship.

H4: Gender is a significant predictor of obstinate partisanship.

H5: Education is a significant predictor of obstinate partisanship.

H6: Income level is a significant predictor of obstinate partisanship.

H7: Area of residence is a significant predictor of obstinate partisanship.

H8: Offline political discussion is a significant predictor of obstinate partisanship.

H9: Online political discussion is a significant predictor of obstinate partisanship.

H10: Discussion disagreement is a significant predictor of obstinate partisanship.

Methodology

The data was collected in person through a survey questionnaire from a diverse sample of citizens (N= 315) representing wider segments of society belonging to different professions: govt. servants 15.9%, private organization employees 17.1%, Businesspersons 28.3%, professionals 18.4%, homemakers 6.3%, students 6.7%, and others 7.3%. The sample was drawn 70% from the urban population, i.e., Lahore, Rawalpindi, Karachi, and Islamabad and 30% from rural areas (14.6%) and small towns (17.5%) surrounding the cities. Ten independent variables, including; five demographics, one media use habit, one party affiliation, and three political discussion variables, were examined for their influence in obstinate partisanship in individuals.

Data Analysis and Results

Descriptive Statistical Analyses

Demographic Variables

Five demographic variables manifested in the sample are as follows: age (M = 40 years, SD = .75), gender (87.3% male), education 80% below college level (SD= .724), income 70% less or equal Rs.50, 000 (M= 2.12, SD= 0.87) where 1 = less than 25000, 2= 25000-50000, 3= 50000-75000, 4= 75000-1lac, 5= more than 1lac) and the majority city dwellers (70%).

Media Use Habits

Table 1 shows the participants’ responses for each media platform. The most frequently used medium is Facebook (M=2.23, SD= 0.53), and WhatsApp (M= 2.20, SD= 0.50). Television comes after the two social networking sites. Google is used less than Facebook and WhatsApp. Reading newspapers and magazines is not common. Radio, it seems, is not a choice in the list of available media. The overall pattern as Figure 1 shows the general preference media platform use.

Table

1. Percentage responses to

the frequency of media use

|

|

Do not use |

Use 2-3 hours |

More than 4 hours |

|

Radio |

93.7 |

6 |

0.3 |

|

Newspapers |

64.4 |

34 |

1.6 |

|

Magazines |

62.5 |

35.6 |

1.9 |

|

Facebook |

5.1 |

66.3 |

28.6 |

|

WhatsAap |

4.4 |

71.1 |

24.4 |

|

Television |

2.2 |

78.1 |

19.7 |

|

Google |

6.3 |

80.6 |

13 |

To assess the trends of media consumption traditional and internet based media platforms were summed and analyzed separately. Internet based media use (Cronbach’s ? = .679, M = 2.16, SD = 0.38) and traditional media use (Cronbach’s ? = .436, M = 1.50, SD= 0.27). For further analysis a single variable, Media Use Habits was created by consolidating all the media use items (Cronbach’s ? = .630, M = 2.71, SD = 0.26).

Affiliation with Political Party

A single item asked about participants’ affiliation with any political party. Three options were provided; no affiliation, support a political party, member of a political party with value 1-3, respectively. (M= 2.06, SD= .281). Majority of the participants, i.e. 91.7% claimed that they are not the member of any political party, but they support a particular party. Only 1% responded that they are formal members of a political party. The remaining 7.3% had no affiliation of any sort with political parties.

Off-line and Online Political Discussion Frequency

Offline Political Discussion Frequency Index was created by consolidating the six items used to measure how frequently respondents discuss politics in their face to face conversations with their spouse, other family members, relatives, friends, acquaintances, and strangers. The responses were measured on 5 points Likert scale from 1= never to 5= all the time. (Cronbach’s ? = .762, M = 2.45, SD = 0.49). Friends turned out to be the most frequent political discussion partners. In a similar manner, Online Political Discussion Frequency was measured. Online Political Discussion Frequency Index was created by consolidating the similar items as for face to face political discussion was asked to measure online conversation about politics. (Chronbach ? = .786, M = 2.24, SD = 0.52).

Discussion Disagreement

Two items measuring the nature of political talk were; “How many times you discuss politics with people whose a) Political views are similar to yours?; b) Political views are different to yours? The responses for the similar views discussant were rarely 33.3%, sometimes 50.2%, and often 16.5% (M =3.17, SD = .77); and for differing views discussant was rarely 34.6%, sometimes 47.3%, and often 18.1%, (M = 2.77, SD = .81) on a 3 point Likert scale. A subtractive index was created by subtracting the frequency of discussion with the people having similar views from the frequency of discussion with the people having differing views (Gil de Zúñiga, 2017). The items were recorded assigning highest value to the highest frequency of disagreement (1 = never to 5 = all the time); (Cronbach’s ? = .748, M = 2.97, SD = 0.70).

Dependent Variables

Obstinate Partisanship

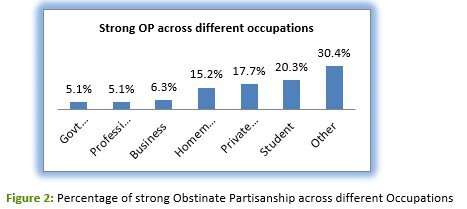

The extreme partisan attitude of obstinately supporting one’s political party policies overlooking the merit. The scale to measure party loyalty was adopted from literature (Ardevol-Abreu & Gil de Zúñiga, 2020). The three statements used to assess party loyalty were directed to the respondents’ subjective feelings without any external reference to be taken as a benchmark. The statements were; “I will always vote for the same political party, no matter what they do,” “I support my political party, even when they make a mistake,” and “being loyal to my party is important, both when they are doing well and not so well”. The responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. (Cronbach’s ? = .68, M = 2.35, SD = .854). Among all respondents, 70.2 % disagreed with the statements; 15.2 % chose neutral; 11.7% agree, and 2.9% strongly agree with the statements. In the Figure, it can be seen that obstinate partisanship is an attitude more prevalent among students and less educated non-professional sections of society as compared to professionals, businesspersons or the formally employed.

Bivariate Correlations between Study Variables

Bivariate correlations between all main variables are presented in Table 3. Age, media use habits, political discussion variables showed a statistically significant, positive relationship with obstinate partisanship, while gender, education and party affiliation showed a statistically insignificant negative association with obstinate partisanship.

The results were statistically significant, positive correlation between the three discussion variables and obstinate partisanship. Offline political discussions showed statistically significant, weak positive correlation with obstinate partisanship (r = .184, p < .000); while online discussions showed statistically significant, moderate positive correlation with obstinate partisanship (r = .403, p < .000), explaining 3.3% and 16.24% of the variation in obstinate partisanship, respectively. Discussion disagreement showed statistically significant, moderate positive correlation with obstinate partisanship (r = .468, p < .000) explaining 21.90% of the variation in obstinate partisanship.

The results were statistically significant, weak positive correlation between media use habits and obstinate partisanship (r = .225, p < .000) with media use explaining 5% of the variation in obstinate partisanship. Among the demographic variables Age (r = .192, p < .001) and income level (r = .129, p < .05) showed statistically significant, weak positive correlation with obstinate partisanship explaining 3% and 1.6% of the variation in obstinate partisanship.

Table

2. Correlation coefficients

for Study Variable

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

0 |

1 |

|

Age |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender |

.229** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education level |

164** |

073 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monthly Family Income |

426** |

.065 |

359** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Area of residence |

.139* |

.158** |

.203** |

.270** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Political Party Affiliation |

.030 |

118* |

.043 |

.163** |

060 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Media Use Habits |

.140* |

203** |

112* |

169** |

.116* |

.057 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Off-line Political Discussion |

303** |

.185** |

170** |

351** |

.198** |

.200** |

157** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

On-line Political Discussion |

173** |

.085 |

096 |

350** |

.173** |

.167** |

424** |

578** |

1 |

|

|

|

Discussion Disagreement |

191** |

.065 |

123* |

302** |

.075 |

.047 |

338** |

322** |

415** |

1 |

|

|

Obstinate Partisanship |

192** |

.035 |

.027 |

129* |

023 |

.096 |

255** |

184** |

403** |

468** |

1 |

**p < .01 (2-tailed); *p <.05 (2-tailed); N=

315

Main Analysis

Multiple linear regressions were conducted to determine how various factors can influence obstinate partisanship in an individual. It was hypothesized that socio-economic demographic factors, media use habits, political discussion variables and party affiliation could affect to a varying degree. To test this hypothesis, multiple regression analysis is used. Results show a suggesting that 31.6% of the variation in obstinate partisanship can be accounted for by the ten factors, collectively, (F (10,304) = 14.453, p < .000), with R2 = 0.322, R2Adjusted = .300. Looking at the unique individual contributions of the predictors, the result shows that Online Political discussions (?= 0.505, t= 4.650, p = .000) and Discussion Disagreement (?= 0.439, t= 6.662, p = .000) positively predict Obstinate partisanship. Furthermore, results indicate that Age also contribute significantly towards Obstinate partisanship (?= 0.215, t= 3.356, p= .001). The data suggests that the individuals who engage in political talk online and disagreements during discussions over political issues are more likely to remain unconditionally supportive of party policy and action regardless of their adequacy and effectiveness of the policy and party performance, and this disposition likely to increase with age.

Table 3. Summary

of the findings of the ten variables regressed on Obstinate Partisanship

|

Hypothesis |

Regression

Weights |

B |

SE |

? |

t-value |

p |

Hypothesis Supported |

|

H1 |

Age ? OP |

.215 |

.064 |

.189 |

3.356 |

.001 |

Yes |

|

H2 |

Gender ?OP |

.106 |

.133 |

.041 |

.801 |

.424 |

No |

|

H3 |

Education ?OP |

-.087 |

.061 |

-.074 |

-1.433 |

.153 |

No |

|

H4 |

Income ? OP |

-.096 |

.059 |

-.098 |

-1.635 |

.103 |

No |

|

H5 |

AOR ?OP |

.091 |

.056 |

.083 |

1.625 |

.105 |

No |

|

H6 |

PPA ?OP |

-.218 |

.149 |

-.072 |

-1.463 |

.145 |

No |

|

H7 |

MUH ?OP |

.228 |

.188 |

.070 |

1.213 |

.226 |

No |

|

H8 |

OFPD ?OP |

-.210 |

.107 |

-.121 |

-1.961 |

.051 |

No |

|

H9 |

ONPD ?OP |

.505 |

.109 |

.306 |

4.650 |

.000 |

Yes |

|

H10 |

DD ?OP |

.439 |

.066 |

.365 |

6.662 |

.000 |

Yes |

Area of

Residence = AOR

Political Party Affiliation = PPA

Media Use Habits = MUH

Off-line Political Discussion = OFPD

On-line Political Discussion = ONPD

Discussion Disagreement = DD

Discussion

The aim of this study was to understand the relationship between various factors contributing to individuals’ partisan behavior. The average participant in the sample happened to be male, 40 years of age with education below college level, and a monthly income less than PKR. 50,000, and living in a city. The data also revealed that Facebook and WhatsApp are the most preferred media choice of the participants, followed by Television. It is found that people are not in the habit of reading, and that might be the reason that newspapers and magazines are not consumed much. Less use of Google as compared to social media sites could be for the same reason.

Ten variables, including media use habits, affiliation with a political party, three discussion variables (offline and online political discussion frequency, discussion disagreement), and five demographic characteristics (age, gender, education, income, and area of residence), were hypothesized to have a significant influence on individuals’ obstinate partisanship. Out of ten, only three hypotheses were supported, as shown in table 3. The results revealed that age, frequency of online political discussion and discussion disagreement are the major predictors of obstinate partisanship in an individual.

Overall, the findings provide a cross-sectional view of the influence various socio-demographic characteristics and engagement with politics because media have on individuals. Data shows that the majority of the participants claimed to support a political party of their choice but are not formally affiliated with them. The data revealed that although having a strong party affiliation by being a member does not necessarily turn into obstinate partisanship, but still has a significant positive correlation with obstinate partisanship. Out of all the socio-demographic characteristics, it is found that only age significantly impacts obstinate partisanship. Obstinate partisanship is likely to increase significantly with the years of age. Income also appears to have a significant positive association with obstinate partisanship, but its presence does not predict the same. Moreover, it is observed that obstinate partisanship is an attitude more prevalent among students and less educated non-professional sections of society. Although education is not a predictor of obstinate partisanship and is found to have an insignificant negative association with extreme partisan attitudes, an increase in education may diminish obstinate partisanship. Being female is also not a predictor of obstinate partisanship and is found to have an insignificant negative association with extreme partisan attitudes. In other words, women are less likely to be obstinate partisans. The area of dwelling does not predict obstinate partisanship and does not seem to impact partisan attitudes. Furthermore, it is observed that media use habits may not directly lead to obstinate partisanship but has a significantly strong correlation with obstinate partisanship. It mediates political discussion, which in turn impacts partisan attitudes.

Two discussion variables related to the frequency and nature of online political discussion turned out to be the most significant predictors of obstinate partisanship among the discussants. It was found that participants prefer to discuss politics mostly with their friends having similar political views. These findings aptly align with the echo chamber effect. As anticipated, when individuals spend more time engaged in discussions with like-minded discussion partners and do not encounter disagreements, their views are reinforced and strengthened, resulting in extreme partisan views as conflicting views are barred out. This has the potential to turn into obstinate partisanship. When such individuals who mostly interact within their homophilous groups forming echo chambers meet differing views, they become defensive and adhere to their views staunchly and unquestioningly. The regression analysis showed that offline political discussion is negatively associated with extreme partisanship, but online political discussion and political disagreement likely to contribute significantly towards extreme behavior, i.e. obstinate partisanship regardless of merit. The offline political discussion as a non-predictor of obstinate partisanship is in line with the outcomes suggested by the theory of homophily creating echo chamber effect regarding political viewpoints. A possible explanation of this could be that strong rational argument cannot be ignored and denied in the face to face political discussions. However, in an online discussion on social media, one can easily avoid opposing voices and can comfortably stay in one’s echo chambers that reinforce one’s beliefs and opinions.

The disagreement in online discussion as a predictor of unconditional partisanship can partially be attributed to the repulsion effect, i.e., when individuals engage in discussion with not likeminded people and come across differing views, they tend to move their arguments in the opposing direction and obstinately reject even rational arguments (Gastil, Black, & Moscovitz, 2008).

Conclusion

This study provides an understanding of the influence of the factors such as media use, socio-demographic characteristics, and kind of political discussions on partisan attitudes of individuals. The first main inference from the data was that media use habits are significantly related to partisanship attitudes but are not predictors of obstinate partisanship. Time spent on social media is almost double that spent on traditional media sources. Participants largely get their news from Facebook, WhatsApp and Television. Individuals who mostly interact online form homophilous groups as they can easily avoid opposing voices on social media, thus comfortably staying in their own echo chambers and reinforcing their beliefs and opinions. Secondly, partisanship is not associated with party membership. A person who is not formally associated with any political party may also behave as an obstinate partisan. Thirdly, it is observed that people, in general, do not frequently engage in political discussions either online or offline. However, if they do engage in such discussions and then encounter disagreements, it may encourage obstinate partisanship. Furthermore, among socio-demographic characteristics, age is a strong predictor of obstinate partisanship; that is, as the age increases, the individuals are more likely to hold extreme partisanship attitudes and become obstinate partisans. It is observed that obstinate partisanship is an attitude more prevalent among students and less educated non-professional sections of society. Lastly, online political discussions and disagreements during discussions are strong predictors of obstinate partisanship.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The limitations of this study are also the gaps left in the wake of this study. The current research focused on the overall use of media platforms for the consumption of political news was examined rather than the specific sources for political information. For future research, it is recommended that the opinion leaders of the media users should be studied as well as their influence in relation to evoking partisanship attitudes among their followers. A separate study with a bigger sample size should be conducted, which focuses only on the masses, such as uneducated laborers and shopkeepers, in order to verify the findings regarding the prevalence of obstinate partisanship among the underprivileged, uneducated masses and the educated and privileged.

References

- Ardevol-Abreu, A., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2020).

- Bae, S. Y., Kwak, N., & Campbell, S. W. (2013). Who will cross the border? The transition of political discussion into the newly emerged venues. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(5), 2081-2089. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.006.

- Bartle, J., & Bellucci, P. (2014). Introduction. In J. B. (Eds.), Political parties and partisanship: Social identity and individual attitudes (pp. 1- 25). New York: NY: Routledge/ECPR

- Baumann, F., Lorenz-Spreen, P., Sokolov, I. M., & Starnini, M. (2020). Modeling echo chambers and polarization dynamics in social networks. Physical Review Letters,

- Boutyline, A., & Willer, R. (2016). The Social Structure of Political Echo Chambers:Variation in Ideological Homophily in Online Networks. Political Psychology, xx(xx). doi: 10.1111/pops.12337.

- Butler, D., & Stokes, D. E. (1974). Electoral change in Britain. London: UK: Macmillan.

- Cebrian, M., Rahwan, I., & Pentland, A. (2016). Beyond viral. Commun. ACM, 59(4):36-39.

- Centola, D. (2013). The spread of behavior in an online social network experiment. Science, 329(5996), 1194.

- Centola, D., & Macy, M. (2007). Complex contagions and the weakness of long ties. American Journal of Sociology, 113(3), 702-34.

- Chen, T., Shi, J., Yang, J., Cong, G., & Li, G. (2020). Modeling Public Opinion Polarization in Group Behavior by Integrating SIRS-Based Information Diffusion Proces. Complexity, vol. 2020, Article ID 4791527,

- Dilliplane, S. (2011). All the news you want to hear: The impact of partisan news exposure on political participation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(2), 287-316. doi:10.1093/poq/nfr006.

- Du, S., & Gregory, S. (2017). The echo chamber effect in Twitter: does community polarization increase? In G. S. In: Cherifi H., Complex Networks & Their Applications V. COMPLEX NETWORKS 2016. Studies in Computational Intelligence, (693). Springer, Cham.

- Dubois, E., & Blank, G. (2018). The echo chamber is overstated: the moderating effect of political interest and diverse media. Information, Communication & Society, 21:5, 729-745, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1428656.

- Gastil, J., Black, L., & Moscovitz, K. (2008). Ideology, attitude change, and deliberation in small face-to face groups. Political Communication, 25(1), 23-46. doi:10.1080/10584600701807836.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2017). Attributes of interpersonal political discussion as antecedents of cognitive elaboration. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas,157(1) 65-84. doi:10.5477/cis/reis.157.65.

- Gonzalez-Bailon, S., Borge-Holthoefer, J., Rivero, A., & Moreno, Y. (2011). The dynamics of protest recruitment through an online network. Scientific Reports, 1, 1-7.

- Guess, A., Nyhan, B., Lyons, B., & Reifler, J. (2018). Avoiding the Echo Chambers about Echo Chamber:Why selective exposure to like-minded political news is less prevalent than you think. Miami: Knight Foundation

- Hargittai, E., Gallo, J., & Kane., M. (2008). Cross- ideological discussions among conservative and liberal bloggers. Public Choice, 134(1- 2):67-86.

- Huckfeldt, R., Mendez, J. M., & Osborn, T. (2004). Disagreement, ambivalence, and engagement: The political consequences of heterogeneous networks. Political Psychology, 25(1), 65-95.

- Jamieson, K., & Cappella, J. (2008). Echo Chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the Conservative Media establishment. London: Oxford UP.

- Kanji, M., & Archer, K. (2002). The Theories of Voting and Their Applicability in Canada. In J. Everitt, & B. O'Neill, Citizen Politics: Research and Theory in Canadian Political Behaviour (pp. 160-183). Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press.

- Lemert, J. B. (1984). News context and the elimination of mobilizing information: An experiment. Journalism Quarterly, 61, 243- 249. doi:10.1177/107769908406100201.

- Mutz, D. (2002a). Cross-cutting social networks: Testing democratic theory in practice. American Political Science Review, 96(1), 111- 126. DOI:

- Perrella, A. (2010). Overview of Voter Behaviour Theories. In E. H. MacIvor, Election (pp. 221- 249). Toronto: Emond Montgomery Publications.

- Price, V. C. (2002). Does disagreement contribute to more deliberative opinion? . Political Communication, 19(1), 95-112.

- Romero, D., Meeder, B., & Kleinberg, J. (2011). Differences in the mechanics of information diffusion across topics: Idioms,political hashtags, and complex contagion on Twitter. Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on World Wide Web, (pp. 695- 704).

- Sîrbu, A., Loreto, V., Servedio, V. D., & Tria, F. (2013). Opinion dynamics with disagreement and modulated information. Journal of Statistical Physics, vol. 151, no. 1-2, pp. 218- 237.

- Smith, D. R., & Mackie, D. M. (2007). Social psychology. Hove: UK: Psychology Press.

- Sunstein, C. (2002). The Law of Group Polarization. Journal of Political Philosophy, 10, 175-195.

- Tsang, A., & Larson, K. (2016). The Echo Chamber: Strategic Voting and Homophily in Social Networks. In K. T. J. Thangarajah (Ed.), Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems (AAMAS 2016) (pp. 368- 375). Singapore: International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems

- Vraga, E. K., Anderson, A. A., Kotcher, J. E., & Maibach, E. W. (2015). Issue-specific engagement: How Facebook contributes to opinion leadership and efficacy on energy and climate issues. . Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 12(2): 200-218. doi:10.1080/19331681.2015.1034910.

- Yardi, S. b. (2010). Dynamic debates: An analysis of group polarization over time on twitter. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society, 20:1-8.

- Yoo, S. W., & Zúñiga, H. G. (2019). The role of heterogeneous political discussion and partisanship on the effects of incidental news exposure online. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 16, 20-35.

- Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Chen, T., & Shi, J. (2020). Agent-based modeling approach for group polarization behavior considering conformity and network relationship strength[J]. Concurrency And Computation-Practice & Experience, 32(14), Article ID e5707.

Cite this article

-

APA : Iftikhar, I., Sultana, I., & Adnan, M. (2021). Political Discussions on Social Media in Pakistan and Obstinate Partisanship. Global Political Review, VI(I), 121-131. https://doi.org/10.31703/gpr.2021(VI-I).11

-

CHICAGO : Iftikhar, Ifra, Irem Sultana, and Malik Adnan. 2021. "Political Discussions on Social Media in Pakistan and Obstinate Partisanship." Global Political Review, VI (I): 121-131 doi: 10.31703/gpr.2021(VI-I).11

-

HARVARD : IFTIKHAR, I., SULTANA, I. & ADNAN, M. 2021. Political Discussions on Social Media in Pakistan and Obstinate Partisanship. Global Political Review, VI, 121-131.

-

MHRA : Iftikhar, Ifra, Irem Sultana, and Malik Adnan. 2021. "Political Discussions on Social Media in Pakistan and Obstinate Partisanship." Global Political Review, VI: 121-131

-

MLA : Iftikhar, Ifra, Irem Sultana, and Malik Adnan. "Political Discussions on Social Media in Pakistan and Obstinate Partisanship." Global Political Review, VI.I (2021): 121-131 Print.

-

OXFORD : Iftikhar, Ifra, Sultana, Irem, and Adnan, Malik (2021), "Political Discussions on Social Media in Pakistan and Obstinate Partisanship", Global Political Review, VI (I), 121-131

-

TURABIAN : Iftikhar, Ifra, Irem Sultana, and Malik Adnan. "Political Discussions on Social Media in Pakistan and Obstinate Partisanship." Global Political Review VI, no. I (2021): 121-131. https://doi.org/10.31703/gpr.2021(VI-I).11